New climate analysis from RMI finds that by encouraging better-located, less car-dependent communities, we can solve the nationwide housing shortage while dramatically cutting pollution.

February 16, 2024

By Jacob Korn, Jackie Lombardi, Raghav Muralidharan, Zack Subin, Anna Zetkulic, Heather House, Rushad Nanavatty LINK To Full Article HERE

Solving the US carbon pollution problem requires much more efficient and equitable use of its urban and suburban land. This means, first and foremost, more housing production in less car-dependent places. There are many policies that can help realize this — including ending exclusionary zoning; deregulating and pricing parking; eliminating minimum lot sizes, unit sizes, and setback requirements; legalizing accessory dwelling units (ADUs); and building permitting reform.

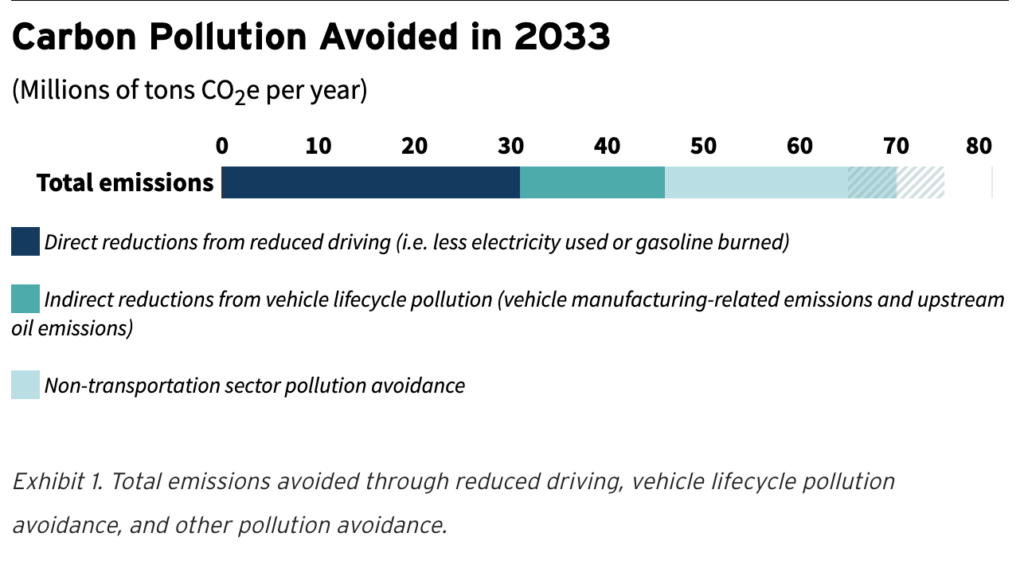

About one-half of the pollution reduction associated with increasing conveniently-located housing would come from reduced travel: cars burning less gas and consuming less electricity. One-third would come from reduced vehicle manufacturing and upstream oil production. The remainder would come from preservation of natural carbon sinks that would otherwise be lost to sprawl and more efficient, less material-intensive buildings.

The case for statewide land use reform as a climate action tool

Globally, urban sprawl is directly or indirectly responsible for one-third of all greenhouse gas (GHG) pollution but is generally overlooked as a major contributor to the climate crisis. It spurs longer travel distances, greater car dependency, more embodied carbon in the built environment, less efficient buildings, more land consumption, and increased loss of natural carbon sinks.

Efficient urban and suburban development is one of the most powerful levers for climate action — in addition to its importance in addressing our cumulative shortage of 4 million homes (this is the current shortfall based on decades of underbuilding — we might need to build as many as 16 million homes on top of that to keep up with ongoing growth over the next decade). Compact, mixed-use communities mean shorter travel distances, more physical activity and improved health outcomes, more housing affordability, less construction material, more energy-efficient buildings, and less land and water consumption.

However, many local and state land use regulations incentivize the opposite. While we don’t yet have a national census of municipal zoning, an estimated 80 to 90 percent of American cities’ developable land is zoned exclusively for detached single-family housing. And even where construction of other home types is allowed, other restrictions, lengthy permitting timelines, excessive infrastructure-related fees for anything other than single-family homes, or other onerous approvals add to project costs and decrease the likelihood of homes being built.

Many municipalities have reformed or are working to reform their land use policies, but action at the state level offers a faster path to bigger impact. It creates the opportunity to build broader coalitions and helps prevent local officials from getting bogged down in local political battles.

We analyzed three categories of pollution avoidance from land use reform: (1) Direct pollution avoidance from less driving, (2) indirect vehicle lifecycle pollution avoidance, and (3) rougher estimates for pollution avoidance from non-transportation sectors. “Direct pollution avoidance” considers emissions from gasoline and electricity consumption from vehicle operation. “Indirect vehicle lifecycle pollution” factors in emissions from vehicle manufacturing and upstream fuel production, averaged per mile over vehicle lifetime. The “non-transportation sector” estimates consider pollution avoidance associated with improved building energy efficiency, less construction material (and its associated embodied carbon), and preservation of natural land sinks otherwise lost to sprawl.

Land use reform could help us achieve direct pollution avoidance of 31 million tons of CO2e per year in 2033 — equivalent to nearly 30 percent of the country being covered by California’s ZEV target (i.e., 100 percent of passenger vehicle sales are ZEVs by 2035). When also considering other vehicle lifecycle and non-transportation sector pollution, the 70 million tons of CO2e per year in avoided pollution would amount to 60 percent of the emissions reductions that would result from all states adopting California’s ZEV target.

Most states have opportunities to address their housing shortages by encouraging construction in convenient, well-connected, amenity-rich locations. The difference to people would be profound; on average in the compact development scenario, people living in the new housing would be able to drive 40 percent less than the average for their states under BAU (i.e., if that housing were built in less convenient locations). Some states — those with large housing shortages — could see an overall per capita VMT reduction of over 9 percent, averaged over both new and existing housing (whose residents’ driving patterns are assumed unchanged in this analysis).

LINK To Full Article HERE

Founded in 1982 as Rocky Mountain Institute, RMI is an independent, non-partisan, nonprofit that transforms global energy systems through market-driven solutions to align with a 1.5°C future and secure a clean, prosperous, zero-carbon future for all.