As the Ogallala Aquifer dwindles, rural towns try to keep their sole water source. The Ogallala Aquifer s.pans eight states: Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, & Wyoming. It contains the nation’s largest underground store of fresh water. It supports 20% of the nation’s wheat, corn, cotton and cattle production and eepresents 30% of all water used for irrigation in the United States.

KS USGS is tracking water levels

In Moscow, KS, Brownie Wilson pulls off a remote dirt road right through a steep ditch and onto a farmer’s field. He hops out of his white Silverado pickup, mud covering nearly all of it except the Kansas Geological Survey logo stuck on the side with electrical tape. Dry cornstalks crunch under his work boots as he makes his way to a decommissioned irrigation well. He unspools a steel highway tape measure a few feet at a time and feeds it into the well until gravity takes over. He keeps a thumb on it to control the speed. How much of the tape comes out wet lets him calculate how much water has been lost here.

Wilson crisscrosses western Kansas every January to measure wells and track the rapid decline of the Ogallala Aquifer, which contains the nation’s largest underground store of fresh water.

Last year, some wells had dropped 10 feet or more because of the severe 2022 drought. But this year, they stayed about the same or dropped a couple feet. Some of these wells have dropped more than 100 feet since Wilson started working for the agency in 2001, he said.

“But I do think we can peck away at it and make some headway.”

Irrigation is one big contributor

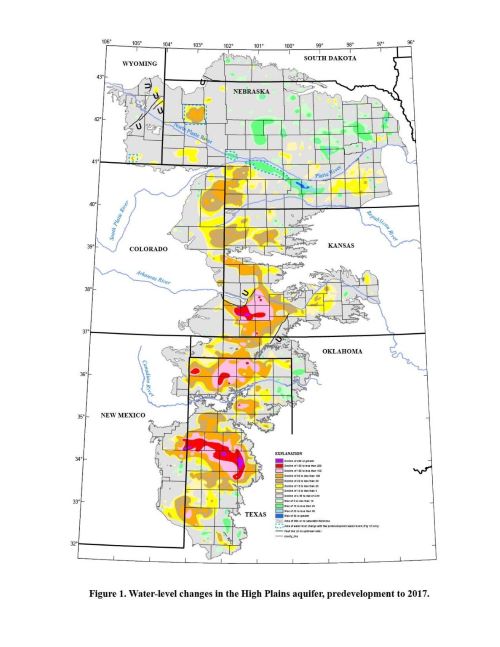

The Ogallala Aquifer, the underground rock and sediment formation that spans eight states from South Dakota to the Texas Panhandle, is the only reliable water source for some parts of the region. But for decades, states have allowed farmers to over pump groundwater to irrigate corn and other crops that would otherwise struggle on the arid High Plains.

Now, the disappearing water is threatening more than just agriculture. Rural communities are facing dire futures where water is no longer a certainty. Across the Ogallala, small towns and cities built around agriculture are facing a twisted threat: The very industry that made their communities might just eradicate them.

Water levels in Texas, where the Ogallala runs under the state’s panhandle, have dropped 44 feet. New Mexico has seen a 19.1-foot decline. In Colorado, Nebraska, Oklahoma and Wyoming, the water level has declined less than the eight-state average, while in South Dakota it has risen.

Depletion is forcing aquifer-dependent communities across the region to dig deeper wells, purchase expensive water rights from farmers, build pipelines and recycle their water supplies in new ways to save every drop possible.

Since the mid-20th century, when large-scale irrigation began, water levels in the stretches of the Ogallala underlying Kansas have dropped an average 28.2 feet farther below the surface, far worse than the eight-state average of 16.8 feet.

Not just the Ogallala Aquifer

While the Ogallala Aquifer presents distinct circumstances, tensions over groundwater are growing across the country, said climate scientist and author Peter Gleick, who founded the Pacific Institute, a global water think tank.

“You’re not alone,” Gleick told Kansas irrigators and policymakers at the Governor’s Conference on Water, held in November in Manhattan, Kansas. “A lot of the issues that you’re dealing with in Kansas, they’re dealing with in Arizona, and the Colorado (River) basin.”

Without drastic measures, some communities may not survive.

Read the complete article by Kevin Hardy, Stateline and Allison Kite published January 29th, 2024 at 11:53 AM in Flatland HERE.

This story, the first in an occasional series about water challenges facing the American heartland, is a partnership between Stateline and the Kansas Reflector. Kevin Hardy covers business, labor and rural issues for Stateline from the Midwest. Allison Kite is a data reporter for the Kansas Reflector, where this story first appeared, with a focus on the environment and agriculture.